THE

BIOGEOGRAPHER

Newsletter of the Biogeography Specialty Group

of the Association of American Geographers

Electronic Version Volume 5 No. 2 Spring 2005

BSG Board: John Kupfer (President) LesleyRigg, Joy

Wolf, Mary Ann Cunningham, and David Cairns

Ex officio: Taly Drezner (Secretary-Treasurer), Duane Griffin

(Editor).

In this issue:

President's Column

Confessions of a Generalist Living in a Specialists’

World

Every now and then, it’s worth taking stock of one's own research

interests and activities, including not only our current interests but

how our research focus has changed through time, how our activities

form a “consistent” research program (if it all), and how our work fits

into the scientific and societal circles within which we participate.

Many of us, for example, were careful to identify the broader relevance

or significance of our dissertation research as we completed graduate

school and hit the job trail. Those of us who are faculty members also

have to do so when we come up for tenure or promotion and are asked to

characterize the central nature or focus of our research activities.

Several things in the past few months have caused me to once again

reflect on my own body of research, and I’ve come to the conclusion

that: “I’m a weed!”. OK, I’m not a weed in the agricultural sense of

the word, but rather a weed in the sense of being a generalist in what

is increasingly becoming a specialists’ world. This, as I hope to point

out in the next few paragraphs, is not necessarily a bad thing, but

rather one end of the spectrum of approaches to research agendas that

can be seen in biogeography (as in other fields) today.

One of the main reasons I’ve been thinking about the nature of my

research is that I applied and interviewed for a position at the Univ.

of South Carolina this past fall, the first time I had done either

since before coming to Arizona. In my earlier job interviews, I was

relatively fresh out of grad school and one of my main objectives was

to show that my work wasn’t so overly specialized as to remove me from

consideration for jobs that didn’t seem to be quite up my alley. As I

put together my application packet last Fall, assembled my job talk,

and thought about things to emphasize on my trip to Columbia, I had

just the opposite experience. In fact, I came to the realization that I

would likely be the most generalized candidate they would interview for

the position. After all, I’ve worked on riparian ecology in the Midwest

and Southeast, montane forest pattern and process in Tennessee,

Arizona, New Mexico and Idaho, invasive species and fire in Arizona

grasslands, and successional dynamics in landscapes in the Midwest,

Southeast and Central America (plus a few other things to boot). I’ve

published on climate change, succession, seed dispersal, remote sensing

techniques, forest fragmentation and a handful of other topics since

starting graduate school 16 years ago, and my work has been by turns

theoretical, conceptual and applied.

The second thing that had me thinking about my place in the

biogeographic universe was looking through the diversity and sheer

number (39!) of BSG sponsored or co-sponsored sessions for the Denver

AAG meeting. Sixteen of those sessions have the roots “Dendro-” or

“Paleo-” in their titles, and we now have full- or even

multiple-sessions on topics like “Landscape Pathology”, “Stable Isotope

Analysis” and “Hurricanes”. I say this certainly not to imply it’s a

bad thing, but rather because it reminds me of the increasingly

specialized nature of our group’s membership. With respect to myself,

I’m basically a field-based community / landscape ecologist, but I know

a little dendrochronology, a fair amount of remote sensing, a pretty

good amount of geospatial analysis, some ecological modeling, and even

a little bit about pack rats. When people are putting together research

teams for large multidisciplinary projects here at the UA, one of my

problems is not having enough of a distinct niche to fill since I’m not

“the remote sensing guy” or “the dendrochronologist” or “the GIS guy”

(there doesn’t seem to be a call for “the ordination guy”, for example).

So, given the inefficiencies of being a generalist (and there are

several), what is it that drives me to keep doing new and slightly

different things? Over the last few months, I’ve found three answers to

this question, the first of which is simply expediency. Wherever you

go, greater proximity to study sites in the local geographic area for

both me and my students means developing new research questions

appropriate to the region. If you move to a lot of new places (and

ecosystems) like I have, you pick up interests just from being there.

In some cases, this might just involve tweaking pre-existing research

projects or interests (e.g., transferring my interests in Midwestern

floodplain forests to southern bottomland hardwood forests after moving

from Iowa to Memphis); in others, it means developing entirely new

interests (e.g., working in montane forest communities in the Smokies

and Rockies).

Second, when you move as much as I have, you not only expand your

research interests with the proximity to new ecosystems and research

sites but also with greater exposure to new people both inside and

outside of the university. This has certainly been the case, for

example, with the grassland research that I’ve been doing in southern

Arizona for almost 4 years now, which stemmed from interactions with

new colleagues here at UA and the Audubon Society. I never set out to

be a grassland ecologist, but the opportunities to study invasive

species effects and grassland species dynamics using manipulative,

controlled experiments (and seeing the results unfold over a few years)

has allowed me to address some of the same questions I’ve been working

on with trees. Similarly, my interactions with people at Arizona like

Andrew Comrie, Gordon Mulligan, Tom Swetnam, Julio Betancourt, Guy

McPherson and many others on the UA campus have gotten me interested in

topics well outside the scope of my previous research and exposed me to

ideas and methods that I’ll take with me when I move to Columbia this

summer.

Finally, part of the answer is that it’s just my basic personality

type to be interested in a broad range of topics and research

activities. As geographers, I think most of us are inclined to have

some generalist tendencies anyway, but I’ve found that my broad range

of experiences has given me different spins on projects than I would

otherwise have had. In my case, I’ve valued the broad range of

experiences that I’ve had while working on projects with not only other

geographers but also with the range of ecologists, botanists, resource

managers, engineers and geoscientists with whom I’ve worked.

When I was at Memphis, an incoming chair of the Biology Department

told one of my friends that his work was “too broadly focused” and that

to really accomplish something meaningful, he needed to “pick one topic

and focus all his efforts on it”. I remember a subsequent comment from

the Chair that went something like this: “Take me, I study the behavior

of voles so every time I see some new and interesting research, I’m

thinking, ‘How can this relate to voles?’.” I see his point and the

many tangible benefits of being more highly specialized, but I also

have come to understand the occasional value of having broad research

interests as well. All of this I guess brings me to the conclusion that

“I’m OK with being a generalist.” It’s not that being a generalist

means I don’t have a central theme to my work (which “stresses the

manners by which spatial patterns of ecological phenomena interact with

and constrain ecological processes such as succession, plant dispersal

or non-native species invasions”, according to the cover letter of my

USC application), but rather that I enjoy and benefit in some ways from

the breadth of projects that I work on around this central theme. In

this respect, I think I’m a lot like Norm Christensen, Peter White and

others who have influenced my scientific and professional thinking.

Finally, there is a third reason I’ve been thinking about these

things. For the upcoming Denver AAG Meeting, Tony Stallins and George

Malanson have put together a panel with Katrina Moser, David Cairns,

Amy Hessl, Al Parker, Jake Bendix, Tom Crawford and Tom Vale on

“Unifying Themes in Biogeography”. Among the tentative list of topics

to be discussed are: What are the themes in your research of

interest/relevance to the broader biogeographical community? How

important is it to have conversations about unifying themes? Should we

ask more epistemological/philosophical questions about our research?

I’d like to close by encouraging you to make this panel discussion if

it fits into your schedule as I think it will stimulate further

discussion on some of the points I’ve made in my final chair’s column.

Election

BSG Board: Vote Now!

Current

BSG members may vote for President and 2 Board Members. Student

members can also vote for the Graduate Student Board Member. Vote

by sending

an e-mail with your choices to bsg-election05@geog.tamu.edu)

before March 31 . Only current

BSG members are eligible to vote. If you are unable to vote via e-mail,

please send your votes by regular mail to:

David M. Cairns

Department of Geography

3147 TAMU

Texas A&M University

College Station, TX 77845

BSG

Board (Vote for 2)

David

R. Butler (Ph.D. University of Kansas, M.S. University of Nebraska,

B.A. University of Nebraska at Omaha) is Professor and Graduate Program

Coordinator in the Department of Geography at Texas State

University-San Marcos. He is interested in ecotones, and the

interface between biogeography and geomorphology. He is author of

the book (Cambridge, 1995) Zoogeomorphology - Animals as Geomorphic

Agents. He has guest edited special issues of Physical

Geography on the topics of alpine treeline (1994) and

environmental change (2001), served on the editorial boards of Landscape

Ecology (1999-2003) and Physical Geography (1996-present),

and has published 25 book chapters, and over 125 refereed papers in

journals and conference proceedings, including Annals of the

Association of American Geographers, The Professional Geography,

Physical Geography, Progress in Physical Geography, Catena, Arctic and

Alpine Research, and others. He serves on the AAG's

Publications Committee, served as Chair of the AAG Mountain Geography

and Geomorphology Specialty Groups, and was the recipient of the

Mountain Geography group's Outstanding Recent Accomplishment Award

(2001) and the Geomorphology group's G.K. Gilbert Award for Excellence

in Geomorphological Research. He teaches courses in Landscape

Biogeography, Geomorphology, and Research Design.

Charles Lafon (Ph.D. and M.S, University of

Tennessee; B.A., Emory & Henry College) is an Assistant Professor

of Geography at Texas A&M University, where he teaches courses in

biogeography, climatology, field geography, and introductory physical

geography. His research employs fieldwork (including

dendrochronology) and simulation modeling to investigate the effects of

fire, ice storms, insect outbreaks, and historic human land use on

patterns of tree species composition and diversity in eastern North

America. He is also interested in the interactions of terrain,

climate, and vegetation that generate spatial patterns in the frequency

and severity of disturbance. He has served the BSG as a judge in

the student research proposal competition, and has published papers in

the Journal of Vegetation Science, Oikos, Physical

Geography, Climate Research, the Journal of Geography,

and Dendrochronologia.

J. Anthony (Tony) Stallins, (PhD University

of Georgia, MS Georgia State University, BS Florida State University)

has been an Assistant Professor of Geography at Florida State

University for the past five years. His research examines how

coastal and riparian biogeomorphic interactions influence vegetation

patterns and how land-use history influences present-day forest

dynamics. His main research locations have been in the

southeastern US, from salt marshes and barrier island dunes, to

longleaf pine sandhills and cypress-tupelo forests. From a disciplinary

standpoint, Tony is interested in how AAG biogeographers can find

common ground among methodological strands that emphasize field-based

description, hypothesis testing, simulation, and reconceptualization of

pattern and process. Tony teaches courses in Environmental

Science, Map Analysis, Physical Geography, and Field Methods. His

publications have appeared in Plant Ecology, Physical

Geography, the Annals, Climatic Change, and Natural

Areas Journal.

Thomas W. Gillespie (Ph.D. University of

California Los Angeles, M.A. California State University, Chico, B.A.

University of Colorado, Boulder) is a sixth year assistant Professor in

the Department of Geography at UCLA. His research interests over

the last six years have focused on testing biogeographic hypotheses

related to patterns of species richness and rarity for a number of taxa

at local, regional, and global spatial scales. . His research focuses

on three primary themes: forest ecosystems, biogeography and

conservation theories, and geographic information systems and remote

sensing. Currently, his research has been in tropical dry forests of

Oceania which have been identified as high priority areas for

conservation. He has published in Ecological Applications,

International Journal of Remote Sensing, Global Ecology and

Biogeography, Journal of Biogeography, Progress in Physical Geography, and

Conservation Biology.

Robert Dull (Ph.D. University of

California, Berkeley, M.A. San Francisco State University, B.A.

University of California, Santa Barbara) is an Assistant Professor in

the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of

Texas, Austin (beginning in fall 2004). Prior to joining the

faculty at UT, Rob spent two years (2002-2004) as an Assistant

Professor at Texas A&M University. He has carried out

research projects both in Central America (El Salvador, Nicaragua) and

the western United States focusing on decadal to millennial-scale

changes in regional vegetation, climate, fire regimes, and land

use. Over the past year Rob has been working on late Holocene

paleoecology and modern forest conservation in Nicaragua (Ometepe

Island, Volcán Mombacho, Rivas), as well as starting new

projects along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Mexico (Veracruz,

Tamaulipas). In addition to intro-level physical geography, Rob teaches

upper division and grad classes in Quaternary paleoecology,

biogeography, natural hazards, and human impacts on the

environment. He has published articles in the Journal of

Biogeography, the Journal of Paleolimnology, Latin

American Antiquity, Geological Society of America Special Papers,

and Quaternary Research.

Amy Hessl (Ph.D. University of Arizona,

M.S. University of Wyoming, B.S. & B.A. University of California,

Berkeley) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geology and

Geography at West Virginia University. She is interested in the

interaction between ecosystem processes and human activities in

forested systems. She has explored aspen forest dynamics in

Wyoming, paleo-fire regimes in central Washington and carbon dynamics

in eastern deciduous forests of West Virginia. Amy teaches

courses in Physical Geography, Biogeography, Environmental Field

Geography and the Geography of Fire. She has published in BioScience,

Climatic Change, Ecological Applications, and Journal

of Biogeography, among others. As a board member, Amy is

particularly interested in broadening the scope and influence of the

BSG within and beyond the AAG.

David Goldblum (Ph.D. University

of Colorado, M.S. University of Colorado, B.A. University of

California, Los Angeles) is an Associate Professor in the Department of

Geography and Geology at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. He is

interested in the potential impact of climate change on forest dynamics

at the ecotone between deciduous forest and boreal forest in the

eastern United States. He has been conducting research on this

question in Ontario, Canada since 1999. Previous projects have

been conducted in Australia, New Caledonia, Colorado, and New York

State. David teaches courses in Biogeography, Forest Geography, Spatial

Analysis, and Human-Environmental Problems. He has published in Physical

Geography, Journal of Vegetation Science, Australian Journal of

Ecology, Journal of Biogeography, Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical

Society, and Plant

Ecology.

Jim Speer (Ph.D., University of Tennessee;

M.S., and B.S. University of Arizona) is an Assistant Professor at

Indiana State University. He specializes in Dendrochronology and

examines disturbance ecology. The recent Brood X emergence of

periodical cicadas provided an opportunity to examine cicada ecology

and how they influence succession through their effect on the

trees. He continues to expand the application of dendrochronology

to new insects, tropical regions, and new methods (such as mast

reconstruction). He has organized the North American

Dendroecological Fieldweeks for three years and has helped to organize

the dendrochronology session at AAG for the past five year. Jim

teaches a wide range of classes including Biogeography, Conservation of

Natural Resources, Quaternary Environments, Soil Genesis and

Classification, Structural Geology, and Fundamentals of Tree-Ring

Research. He has published in Ecology, Climate Research, The

Holocene, Journal of Biogeography, and Tree Ring Research.

Valery J. Terwilliger (Postdocs:

University of California, Santa Barbara; Hebrew University, Givat Ram,

Ph. D. University of California, Los Angeles, M.S. University of

Florida, B.A. McDaniel College) is an Associate Professor at the

University of Kansas. Her interests in the relationships between the

responses of plants to their environments and plant distributions are

both quaternary and present-day. She and her students' recent field

research sites include Utah, Arizona, Kansas, Maryland, Panamá,

and Ethiopia. There is also a lab rat component to her work as stable

isotope methods yield many of the insights for her studies. She teaches

honors courses in Physical Geography, and Human Biogeography, as well

as courses and seminars in Plant Geography, Field Ecology, and Stable

Isotopes in the Natural Sciences. Journals that have published her and

her student's papers include Biotropica, Bulletin of the

Geological Society of America, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Catena,

Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, Vegetatio, New Phytologist,

Earth Science and Planetary Letters, Journal of Plant Physiology,

International Journal of Plant Sciences, International Journal of

Vegetation Science, Progress in Physical Geography, Phytochemistry,

Physical Geography, and American Journal of Botany.

Graduate Student Board

Member (Student BSG Members Vote for 1)

Christopher Gentry (M.A. Indiana State

University, B.A. Indiana University-Southeast) is a Ph.D. student in

the Department of Geography at Indiana University, Bloomington.

At IU he has taught the lecture and laboratory portions of Physical

Systems of the Environment, discussion sections of Introduction

to Human Geography, and has given guest lectures at the School for

Public and Environmental Affairs. His research interests include

dendroecology, landscape and fire ecology, and biogeography. He

is currently researching the effects of changing atmospheric carbon

concentrations and climatic effects on a mixed deciduous hardwood

forest in Indiana. For the past two years he has assisted the

North American Dendroecological Fieldweek and has been a reviewer for Forest

Ecology and Management. He is a regular attendee of BSG

meetings, and a member of the Association for Fire Ecology and Gamma

Theta Upsilon.

Chad Lane (Ph.D. in progress, M.S.

University of Tennessee, B.S. University of Denver) is a Ph.D. student

in the Department of Geography at the University of Tennessee. He

is interested in lake sediment records of the interactions between

climate, vegetation, and human populations throughout the

Quaternary. His main research areas have been the Dominican

Republic and Costa Rica. In his research he uses multiple proxies

to develop detailed records of paleoenvironmental change. In

particular, he uses fossil pollen, charcoal, stable isotope, and other

geochemical analyses to develop these records. Chad’s current

research is focused on identifying the impacts of droughts in the

circum-Caribbean region on both ecological communities and prehistoric

human populations in the interior of the Dominican Republic during the

late Holocene. His past research has included stable carbon

isotope analyses of lake sediments from several lakes in Costa Rica to

identify prehistoric forest clearance and agriculture, natural changes

in vegetation in response to climate change, and changes in

paleolimnological conditions. Chad has published papers in the Journal

of Paleolimnology and has recent submissions to Palynology

and Ecography. During his residence at the University of

Tennessee, Chad has been appointed as a research assistant, a teaching

assistant, and has taught an introductory physical geography course.

President (Vote for 1)

Joy

Nystrom Mast (Ph.D. and M.S. University of Colorado - Boulder,

B.S. University of Wisconsin - Madison) is Chair of the Department of

Geography and Director of the Dendroecology Lab at Carthage College in

Wisconsin. She is interested in forest dynamics of conifer and riparian

ecosystems, focusing on the American Southwest and Rocky

Mountains. Joy currently serves on the National Science

Foundation Geography and Regional Sciences panel and is a consultant

for the National Park Service Southern Colorado Plateau Network for 14

National Parks. She has enjoyed serving the BSG as a executive board

member, as a grant reviewer, and as a student presentation judge, and

is also active in the International Biogeography Society. Joy teaches

courses in Forest Ecology, Biogeography, Biological Conservation, and

field courses in Arizona and Wisconsin. She has received funding for

her research from NSF Biocomplexity program, the National Park Service,

the National Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, among

others. Joy has published in a variety of journals and books,

including Journal of Biogeography, Landscape Ecology,

Ecological Applications, Forest Ecology and Management, Canadian

Journal of Forest Research, Physical Geography, and Journal

of Forestry.

Kimberly E. Medley (Ph.D., M.A., Michigan

State University, B.S. Kent State University).

After a one-year postdoctoral appointment in landscape ecology at the

Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Kim began an academic career at Miami

University (in Ohio), where she just received word that she will be

promoted to Professor of Geography. Under a Worldwide

Women-in-Development fellowship in 1997-1998, she worked as an

ecological monitoring and gender specialist for the U.S. Agency for

International Development in Madagascar. Kim is especially interested

in forest resources and how the physical environment and human

activities influence their geographic patterns of diversity,

environmental histories, and conservation futures. She is the

author of over twenty publications in peer-reviewed journals and books,

and especially enjoys her collaboration with graduate and undergraduate

students on integrative and applied research in Ohio, Kenya, and other

locations. Funded by the National Geographic Society and now

Conservation International, she is conducting an ethnoecological

research project on Mt. Kasigau, Kenya that examines the use of woody

plants by the Kasigau Taita along an altitudinal gradient between

bushland and montane evergreen forest. She is grateful for the

professional support provided by colleagues in the Biogeography

Specialty Group and will hope to carry on that tradition for new and

continuing members.

Back to the top.

News

International Biogeography Society News

The 2005 International Biogeography Society conference met Jan. 5-9,

2005 at the National Conservation Training Center, Shepherdstown WV.

The meeting included poster sessions, symposia, a keynote address

and a workshop on Historical Biogeography. The meeting's theme

"Conservation Biogeography," reflects the fact that conservation is

emerging as one of the dominant themes in the IBS and the broader field

of biogeography. As part of this this trend, Blackwell is "rebranding"

one of the Journal of Biogeography's

sister journals as Diversity and

Distributions, a Journal of Conservation Biogeography. The

journal recently published an article by Robert J. Whittaker and other

members of the Oxford University School of Geography's Biodiversity Research Group's article called "Conservation

Biogeography: Assessment and Prospect" (Diversity

and Distributions Vol.

11, Jan. 2005), which BSG members

should find interesting.

The IBS meeting was organized around the five symposia:

- Biogeographic Responses to Global Change

- Biogeography of Exotic Species

- Geography of Parasites and Infectious Diseases

- Geography of Extinction: From Paleo to Recent Periods

- Biogeography and Ecological Impacts of Human Civilizations.

Each symposium included half-hour presentations by five invited

speakers representing the breadth of

the biogeographical enterprise. Brief descriptions of each symposium

and Richard Field's reflections on the meeting are

available in the IBS newsletter (click here).

Poster sessions supplemented the symposia and highlighted the work

of 120 biogeographers. The meeting culminated with

geographer-turned-librarian and Alfred Russel Wallace scholar Charles

Smith's keynote address on Wallace.

The small size of the meeting (around 100 participants, I'm guessing) and intimate

setting encouraged informal discussions, as did the fact that the posters remained

up for a full day. This meant there was plenty of opportunity and time to read

most, if not all, of the posters and to think about them, discuss them during

breaks, meals, or other downtime, and go back and view them multiple times,

if you wanted to. I've never been to a meeting where I discussed the content

of presentations (my own and other peoples') as frequently or in as much depth

and detail as I did at this one. As was the case with the inaugural IBS meeting

2003, I came away from the conference excited about the discipline of biogeography

and full of new ideas and insights. If there were any way we could create this

level of interaction at AAG meetings, I would lobby for moving heaven and Earth

to make it happen.

One of the high points of the symposia was Hartmut Walter's presentation. Hart

is one of the founding members of the BSG, and one of four biogeographers

in the UCLA geography department (along with ex-BSG president and IBS founding

treasurer Glen MacDonald, Tom Gillespe, and Jared Diamond), and his presentation

generated a great deal of interest and discussion. The abstract of Hart's paper

is reproduced below.

To help further its goal of becoming a truly international society, the next

IBS meeting, scheduled for early January 2007, will move beyond the U.S., to

Oxford, U.K. Membership in the IBS is $40 (Students $30), which includes the

IBS newsletter, discounts on IBS meetings and publications, and eligibility

for a $30 subscription to the online versions of the Journal of Biogeography,

Global Ecology & Biogeography, and Diversity & Distributions

(a personal subscription is $330, so this is a steal!). For more information,

see the IBS web site.

The

Culture and Politics of Extinction: A Geography of Human Folly and Animal Angst

Hartmut S. Walter

UCLA

2nd Biennial Conference, International Biogeography Society, Shepherdstown,

West Virginia, January 5-9, 2005.

The current distribution of biota is a product of a complex of interactive

historic and present-day factors; some of these are anthropogenic in nature.

This paper investigates the contribution of human behavior, beliefs, and policies

that contribute to extinction processes in animals. I am particularly interested

in those cases where incorrect or ecological and geographic assessments of rarity

and extinction probability result in faulty or inefficient conservation management.

It is hoped that biogeography can address this problem by recognizing and incorporating

the complex human-animal interface into future conservation science and management.

One aspect concerns the need to create a firewall between distributional reality

and the partisan needs of motivated stakeholders. Biogeography cannot afford

to support trivial conservation demands when there is an abundance of unmet

and poorly understood conservation needs among noncharismatic taxa around the

world.

Department News

Biogeomorphology at Kentucky

Several members of the University of Kentucky Department of

Geography are involved in projects examining the coevolution of

landforms, soils, and ecosystems, and the effects of trees on

weathering and regolith evolution, in forest environments in the

Ouachita Mountains, Arkansas. Jonathan Phillips (Professor) and Dan

Marion (USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, and Adjunct

Professor of Geography) have been examining the biomechanical effects

of trees on soil variability and regolith evolution, and the relative

importance of biological and lithological influences. Publications on

this work, funded by the USDA Forest Service, have appeared or are in

press in Geoderma, Forest Ecology & Management, Earth Surface

Processes & Landforms, and Journal of Geology. Kristin Adams

recently completed her M.A. thesis in conjunction with this work, and a

number of other Kentucky geography faculty and graduate students, and

Forest Service personnel, have contributed to this ongoing work. The

newest phase of the project is examining in detail the effects of tree

roots on weathering at the bedrock weathering front, with Assistant

Professor Alice Turkington playing a key role. PhD candidate Linda

Martin, in addition to assisting in the Arkansas work, is pursuing her

dissertation (funded by EPA) on evolution of fluviokarst landscapes in

central Kentucky, with the hydrologic and geomorphic effects of trees,

and root-rock interactions at the base of the epikarst, playing a

central role.

Jonathan D. Phillips

New Disciples of Soil

Lexington, Kentucky

(Univ. of Kentucky, Dept. of Geography)

http://ukslsrp.150m.com/JPhome.htm

Member News

Henri Grissino-Mayer

Henri's involvement with the "the mystery of the Messiah," (see here, and here) has launched something of a cottage

industry in forensic biogeography. In the last issue, we highlighted his work

on the (putative) Abraham Lincoln log cabin. Since then, he's

been involved in three more projects, dating the Karr-Koussevitzky 1611 Amati

bass, working on a Texas murder case (see Research Notes below), and dating

another historic cabin. The latter project, Henri promises, "will actually help

re-write Tennessee history and history books." We'll feature it in the next

issue.

Henri on (1611 Amati) Bass

The performances and conducting of Serge Koussevitzky

(1874-1951) gave the world its first serious exposure to the double

bass instrument. In 1962, after hearing a New York Town Hall recital

given by Gary Karr, Koussevitzky's widow, Olga, gave Karr the double

bass used by Serge Koussevitzky, reportedly made by Antonio and

Hieronymous Amati in 1611. The Amati brothers were sons of Andrea Amati

who began the famed Amati line of instrument makers in Cremona, Italy,

in the mid to late 1500s. Nicolo Amati (1596-1684), the son of

Hieronymus, was the mentor of Antonio Stradivari.

The performances and conducting of Serge Koussevitzky

(1874-1951) gave the world its first serious exposure to the double

bass instrument. In 1962, after hearing a New York Town Hall recital

given by Gary Karr, Koussevitzky's widow, Olga, gave Karr the double

bass used by Serge Koussevitzky, reportedly made by Antonio and

Hieronymous Amati in 1611. The Amati brothers were sons of Andrea Amati

who began the famed Amati line of instrument makers in Cremona, Italy,

in the mid to late 1500s. Nicolo Amati (1596-1684), the son of

Hieronymus, was the mentor of Antonio Stradivari.

Today, Gary Karr has been acclaimed as "the world's leading solo

bassist" by Time Magazine, and is considered the first solo double

bassist in history to make playing a full-time career. In 1967, Karr

founded the International Society of Bassists (ISB). In 2004, Karr

stunned the music world by donating the Karr-Koussevitzky 1611 Amati

bass to the ISB, and plans have been made for leading artists to

perform with it at the 2005 ISB Convention in Michigan.

However, close inspection by a top team of experts found stylistic

inconsistencies with the double bass, including the purfling, the top

C-bout channel, the F-holes, and the varnish. Furthermore, the shape of

the instrument itself appears to have been influenced by Stradivari,

who would not be born for another 33 years. The experts reported their

findings to Madeleine Crouch, President of the ISB, who had previously

heard that tree-ring dating had helped solve the mystery of the

"Messiah" violin.

The ISB contacted Henri Grissino-Mayer, and on January 28 and 29,

the Karr-Koussevitzky bass was analyzed in the Laboratory of Tree-Ring

Science at the University of Tennessee. Surprisingly, the double bass

had a continuous series of 297 tree rings on both sides of the

instrument, the most tree rings ever found in a musical instrument,

suggesting the instrument was indeed made in Europe. Dr. Grissino-Mayer

is now comparing the patterns of the tree rings from this instrument

with reference spruce chronologies from the upper elevations of Italian

and Austrian Alps region, the most likely locality of the wood used to

make the instrument.

Henri reports that he does have absolute dates for the tree rings in

the instrument, but has been requested not to release the dates just

yet. If the instrument was indeed made by the Amati brothers in 1611,

the instrument would be priceless because this would be the only double

bass known to have been constructed by the Amati brothers.

Also, Henri, Sally Horn, and Ken Orvis

currently have research featured in an exhibit called "Lost

Worlds: Discovering Past Environments" at the University of

Tennesee's McClung Museum.

Back to the top.

AAG

Biogeographers in Denver

Biogeography Specialty Group Business

Meeting

The BSG business meeting is scheduled for Thursday (4/7/05) from 11:50 AM -

12:50 PM. Bring a lunch and join us.

Physical Geography Reception

A Physical Geography Reception will be held 8-11

PM on

Friday April 8, in the Majestic Ballroom of the Adam’s Mark Hotel. The

reception will feature remarks by AAG Vice-President Dick Marston,

displays by

several publishing houses, and complementary food and drinks. All AAG

members

specializing in an aspect of physical geography (and a guest) are

welcome at

the event. There is no admission charge.

The reception is sponsored by the AAG’s

Cryosphere, Geomorphology,

Climate, Mountain Geography, Biogeography, and Water Resources

Specialty

Groups. In addition to donations by the sponsoring specialty groups,

generous

financial support has been provided by co-sponsors Blackwell Publishing

Inc.,

John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Elsevier Science Ltd., and Bellwether

Publishing

Ltd. A representative from each of these firms will be present, and

books,

journals, and other materials will be on display.

The reception will have two continuous slide shows

running,

similar to the one last year in the “Celebrating a Century of Physical

Geography” reception at the Philadelphia meeting. Reception organizer

Fritz

Nelson requests that physical geographers each send him ONE power

point

slide containing (a) one or more images showing their current research,

and (b)

a one-paragraph annotation or description. Please keep the size

of

individual slides to 6 Mb or less. Send slides to Fritz at recep@geog.udel.edu by March 21. Please ensure that slides are in

final

presentation format—no editing will be done on them.

BSG Sponsored Sessions

This year, we have thirty

BSG-sponsored paper sessions. For details on specific sessions and

papers, go to the AAG's 2005

Annual Meeting Program web page, select "Specialty Group" in the

search criteria, and search on "biogeography."

- Advances in Paleoclimatology I, II, and III: Quantitative,

multiproxy, and novel approaches to climate reconstruction

- Biogeography Illustrated Paper Session

- Dendroclimatology I and II

- Dendroecology

- Dendroecology and Disturbance

- Dendrogeomorphology

- Eastern Forest Dynamics

- Emerging themes in political ecology III: Changing landscapes

and biogeographies

- Exotic Species Invasion Dynamics

- Fire History from Dendrochronology

- Geographic approaches to understanding urbanising landscapes and

urban ecosystems

- Geographic approaches to understanding urbanising landscapes and

urban ecosystems

- Geosystems, Ecosystems, and Wildfires 1: Geomorphic Hazards

- Geosystems, Ecosystems, and Wildfires 2: Soil Factors and Time

- Geosystems, Ecosystems and Wildfires 3: Remote Sensing

Applications to Fire Hazard and Effects Assessment

- Geosystems, Ecosystems, and Wildfires 4: Biotic Effects and

Responses

- Geosystems, Ecosystems, and Wildfires 5: Management Issues

- Hurricanes I: Spatial and Temporal Variability

- Hurricanes II: Paleotempestology

- Hurricanes III: Landfalling Hurricanes and Societal Impacts

- Integrative Dendrochronology: Theoretical Cross-overs to Other

Disciplines

- Landscape Pathology

- Landsurface - Atmosphere Interactions I

- Landsurface - Atmosphere Interactions II and Urban Climate I

- Paleobiogeography I: Pollen and Charcoal Calibration and Analysis

to Reconstruct Fire, Vegetation and Agricultural History

- Paleobiogeography II: Paleo Records of Climate, Geomorphic, and

Vegetation Change from the American and African Tropics

- Paleobiogeography III: Paleoecological Evidence of Prehistoric

Human Activity in the Circum-Caribbean Region

- Paleobiogeography IV: Late Quaternary Climate and Vegetation

Change in Temperate North America

- Prehistory, Geoarchaeology, and Paleobiogeography: prospects for

engagement and synthesis

- Stable isotope analysis of trees: new methods, new uses.

- Tropical rarity: biogeography of endemism in low latitude

environments

- Unifying themes and issues in AAG Biogeography Panel Discussion

- Unifying themes and issues in AAG Biogeography I and II

- Western Forest Dynamics

Field Trips!

Click

here for more information on these and other field trips.

A

Landscape Transect in the Boulder Valley Tuesday, April 5: 8am

– 4pm Organizer/Leader: Paul W. Lander, City of Boulder/University of

Colorado Trip Capacity: 40 Cost/person: $75 (includes transportation,

lunch and handouts)

Rocky

Mountain National Park Thursday, April 7: 7am – 6pm

Organizer/Instructor: William C. Rense Workshop Capacity: 40

Cost/person: $75 (includes transportation, lunch, admission fees and

handouts)

Fire and

Forest Management in the Colorado Front Range Friday, April

8: 8am – 6:30pm Organizer/Leader: Rosemary Sherriff,

University of Colorado – Boulder; Thomas Veblen,

University of Colorado - Boulder Trip Capacity: 32 Cost/person: $70

(includes transportation, lunch and handouts)

Terrestrial

Paleoenvironments of the Front Range Near Denver, Colorado

Friday, April 8: 9am – 5pm Organizer/Leader: Joanna Wright, University

of Colorado - Denver Trip Capacity: 40 Cost/person: $70 (includes

transportation, lunch and handouts).

Back to the top.

Recent BSG Member Publications.

Name in bold is the individual submitting

publications.

Meral Avci

Avci, Meral. 2004. Rhododendrons

and their natural occurences in Turkey. İstanbul Üniversitesi

Edebiyat Fakültesi Coğrafya Dergisi 12: 13-29. (In Turkish, also

English abstract).

Avci, Meral. 2004. The

influence of geographical characteristics on the naming of plants in

Turkey. İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Coğrafya

Dergisi 12: 31-45. (In Turkish, also English abstract).

Matthew Becker

Bekker, M.F. 2004. Spatial variation in the

response of tree rings to normal faulting during the Hebgen Lake

earthquake, southwestern Montana, USA. Dendrochronologia 22:53-9.

Bekker. M.F. 2005. Positive feedback between

tree establishment and patterns of subalpine forest advancement,

Glacier National Park, Montana, USA. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine

Research, in press.

David Butler

Allen, Thomas R., Stephen J. Walsh, David M.

Cairns, Joseph P. Messina, David R. Butler, and George P.

Malanson, 2004. Geostatistics and spatial analysis: characterizing form

and pattern at the alpine treeline. In: GIScience and Mountain

Geomorphology (M.P. Bishop and J.F. Shroder, Jr., eds.), Springer

Verlag - Praxis Scientific Publishing, Heidelberg, Germany, 189-214.

Butler, David R., 2004. Zoogeomorphology. In:

Encyclopedia of Geomorphology, Volume 2 (Andrew Goudie, ed.),

Routledge, London, 1122-1123.

Butler, David R., George P. Malanson, and Lynn

M. Resler, 2004. Turf-banked terrace treads and risers, turf

exfoliation, and possible relationships with advancing treeline. Catena

58(3), 259-274.

Resler, Lynn M., Mark A. Fonstad, and David R.

Butler, 2004. Mapping the alpine treeline ecotone with digital aerial

photography and textural analysis. Geocarto International 19(1), 37-44.

Malanson, George P., David R. Butler, and

Stephen J. Walsh, 2004.Ecological response to global climatic change.

In: WorldMinds: Geographical Perspectives on 100 Problems (Donald G.

Janelle, Barney Warf, and Kathy Hansen, eds.). Kluwer Academic

Publishers, Dordrecht and Boston, 469-473.

Walsh, Stephen J., Daniel J. Weiss, David R.

Butler, and George P. Malanson, 2004. An assessment of snow avalanche

paths and forest dynamics using Ikonos satellite data. Geocarto

International 19(2), 85-93.

Henri Grissino-Mayer

Burckle, Lloyd, and Henri D. Grissino-Mayer.

2003. Stradivari, violins, tree rings, and the Maunder Minimum: a

hypothesis. Dendrochronologia 21(1): 41-45.

Soulé, Peter T., Paul A. Knapp, and Henri D. Grissino-Mayer.

2003. Comparative rates of western juniper afforestation in

south-central Oregon and the role of anthropogenic disturbance.

Professional Geographer 55(1): 43-55.

Grissino-Mayer, Henri D. 2003. Canons for writing and editing

manuscripts. Tree-Ring Research 59(1): 3-10.

Grissino-Mayer, Henri D. 2003. A manual and tutorial for the proper

use of an increment borer. Tree-Ring Research 59(2): 63-79.

Grissino-Mayer, Henri D., William H. Romme, M. Lisa Floyd-Hanna, and

David Hanna. 2004. Climatic and human influences on fire regimes of the

southern San Juan Mountains, Colorado, USA. Ecology 85(6): 1708-1724.

Grissino-Mayer, Henri D., Paul R. Sheppard, and Malcolm K.

Cleaveland. 2004. A dendroarchaeological re-examination of the

“Messiah” violin and other instruments attributed to Antonio

Stradivari. Journal of Archaeological Science 31(2): 167-174.

Huffman, Jean M., William J. Platt, Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, and

Carla J. Boyce. 2004. Fire history of a barrier island slash pine

(Pinus elliottii) savanna. Natural Areas Journal 24(3): 258-268.

Kaennel Dobbertin, Michéle, and Henri D. Grissino-Mayer.

2004. The Bibliography of Dendrochronology and the Glossary of

Dendrochronology: Two new online tools for tree-ring research.

Tree-Ring Research 60(2): 101-104.

Speer, James H., Kenneth H. Orvis, Henri D. Grissino-Mayer, Sally P.

Horn, and Lisa M. Kennedy. 2004. Assessing the dendrochronological

potential of Pinus occidentalis in the Cordillera Central of the

Dominican Republic. Holocene 14(4): 561-567.

Soulé, Peter T., Paul A. Knapp, and Henri D. Grissino-Mayer.

2004. Human agency, environmental drivers, and western juniper

establishment during the late Holocene. Ecological Applications 14(1):

96-112.

Ryan Danby

Danby, R.K. 2003. Birds and mammals of the St.

Elias Mountain Parks: Checklist evidence for a biogeographic

convergence zone. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 117:1-18.

Amy Hessl

Hessl, A. E., McKenzie, D., and Everett, R.

2004. Fire and climatic variability in the inland Pacific

Northwest. Ecological Applications 14(2):425-442.

Hessl, A. E. and D. L. Peterson. 2004. Interannual

variability in aboveground tree growth in Stehekin River watershed,

North Cascade Range, Washington. Northwest Science 78(3): 204-213.

McKenzie, D., S. Prichard, A. E. Hessl, and D.

L. Peterson. 2004. Empirical approaches to modeling wildland fire in

the Pacific Northwest Region of the United States: methods and

applications to landscape simulation. Chapter 7 in A.J. Perera and L.

Buse, eds., Emulating Natural Forest Landscape Disturbances. Columbia

University Press, New York, NY.

Hessl, A. E. 2003. Human interactions with

ecosystem processes: causes of aspen decline in the intermountain West.

In: B. Wharf, D. Janelle and K. Hanson, eds. WorldMinds: Geographical

Perspectives on 100 Problems. Pp. 311-316.

Fagre, D. B., D. L. Peterson and A. E. Hessl. 2003.

Taking the pulse of mountains: ecosystem responses to climatic variability.

Climatic Change 59(1): 263-282.

John Kupfer

Kupfer, J.A. and Miller, J.D. 2005. Wildfire effects

and post-fire responses of an invasive mesquite population: the interactive

importance of grazing and non-native herbaceous species invasion. Journal

of Biogeography 32: 453-466

Kupfer, J.A. and Emerson, C.W. 2005. Remote sensing. In: Encyclopedia of

Social Measurement, Vol. 3. Kempf-Leonard, K. (ed.). Academic Press, San

Diego, pp. 377-383.

Kupfer, J.A. and Malanson, G.P. 2004. The biodiversity crisis. In: WorldMinds:

Geographical Perspectives on 100 Problems. Warf, B., Hansen, K, and Janelle,

D. (eds.). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp. 273-277.

Kupfer, J.A, Webbeking, A.L., and Franklin, S.B. 2004. The effects of landscape

structure on plant regeneration patterns and soil characteristics in shifting

cultivation fields near Indian Church, Belize. Agriculture, Ecosystems and

Environment 103: 509518.

Franklin, S.B., Kupfer, J.A., Grubaugh, J.W. and Kennedy, M.L. 2004. A

multi-taxa analysis of biotic diversity in Natchez Trace State Forest, western

Tennessee. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 93: 31-54.

Franklin, S.B. and Kupfer, J.A. 2004. Forest communities of Natchez Trace

State Forest, western Tennessee Coastal Plain. Castanea 69: 15-29.

Glen MacDonald

Huang, C. MacDonald, G.M. and Cwynar, L.C. 2004.

Holocene landscape development and climatic change in the Low Arctic,

Northwest Territories, Canada. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology,

Palaeoecology 205: 221-234.

Kaufman, D.S., Ager, T.A., Anderson, N.J.,

Anderson, P.M., Andrews, J.T., Bartelein, P.J., Burbaker, L.B., Coats,

L.L., Cwynar, L.C., Duval, M.L., Dyke, A.S., Edwards, M.E., Eiser,

W.R., Gajewski, K., Geisodottir, A., Hu, F.S., Jennings, A.E., Kaplan,

M.R., Kewin, M.W., Lozhkin, A.V., MacDonald, G.M., Miller, G.H., Mock,

C.J., Oswald, W.W., Otto-Blisner, B.L., Porinchu, D.F., Rhland, K.,

Smol, J.P., Steig, E.J., Wolfe, B.B., 2004, Holocene thermal maximum in

the western Arctic (0-180 W). Quaternary Science Reviews 23: 529-560 .

Kremenetski, K. V., Boettger, T., MacDonald, G.

M., Vaschalova, T., Sulerzhitsky, L., Hiller, A. 2004. Medieval climate

warming and aridity as indicated by multiproxy evidence from the Kola

Peninsula, Russia. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology

209: 113-125

Kremenetski, K.V., MacDonald, G.M., Gervais,

B.R., Borisova, O.K., Snyder, J.A. 2004. Holocene vegetation history

and climate change on the northern Kola Peninsula, Russia: a case study

from a small tundra lake. Quaternary International 122: 57-68.

Sheng, Y., Smith,L.C., MacDonald,G.M.,

Kremenetski, K.V., Frey, K.E., Velichko, A.A., Lee, M., Beilman, D.W.

and Dubinin, P. 2004. A high-resolution GIS-based inventory of the west

Siberian peat carbon pool. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 18 (GB3004,

doi:10.1029/2003GB002190): 1-14.

Smith, L.C., MacDonald, G.M., Velichko, A.A.,

Beilman, D.W., Borisova, O.K., Frey, K.A., Kremenetski, K.V., and

Sheng, Y. 2004. Siberian peatlands a net carbon sink and global methane

source since the early Holocene. Science 303: 353-356.

Case, R.A. and MacDonald, G.M. 2003. Tree ring

reconstructions of streamflow for three Canadian Prairie rivers.

Journal of the American Water Resources Association 39: 703-716.

Case, R.A. and MacDonald, G.M. 2003.

Dendrochronological analysis of the response of tamarack (Larix

laricina) to climate and larch sawfly (Pristiphora erichsonii)

infestations in central Saskatchewan. Ecosience 10: 380-388.

Kremenetski, K.V., Velichko, A.A., Borisova,

O.K., MacDonald, G.M., Smith, L.C., Frey, K.E. and Orlova, L.A. 2003.

Peatlands of the Western Siberian lowlands: current knowledge on

zonation, carbon content and Late Quaternary History. Quaternary

Science Reviews 22: 703-723.

MacDonald, G., Kaufman, D., Duvall, M, and

Coates, L. 2003. PARCS: Paleoenvironmental Arctic Sciences - taking the

long view. Arctic Research of the United States 17: 50-58.

Joy Mast

Savage, M. and Mast, J.N., 2005. The fate of

ponderosa pine forests decades after intense crown fire. In press,

Canadian Journal of Forest Research.

Mast, J.N. and Wolf, J. 2004. Ecotonal changes

and altered tree spatial patterns in lower mixed-conifer forests, Grand

Canyon National Park, Arizona, U.S.A. Landscape Ecology 19(2): 167-180.

William Noble

The Aftermath of the Pleistocene in the Upper

Nilgiris of Southern India, 2004, Journal, Bombay Natural History

Society 101 (1): 29-63.

The Nilgiri of Tamil Nadu, India, as a

Distinctive Upland Island, pgs. 401-420, in 2004, Neelam Grover and

Kashi Nath Singh (eds.), Cultural Geography: Form and Process, a

festschrift in honor of Prof. A. B. Mukerji, New Delhi, Concept

Publishing Company, xxxiii, 469 pp.

Jonathan Phillips

Phillips, J.D., and D.A. Marion. 2005.

Biomechanical effects, lithological variations, and local pedodiversity

in some forest soils of Arkansas. Geoderma 124: 73-89.

Phillips, J.D. 2004. Divergence, sensitivity,

and nonequilibrium in ecosystems. Geographical Analysis 36: 369-383.

Phillips, J.D., and D.A. Marion. 2004.

Pedological memory in forest soil development. Forest Ecology and

Management 188: 363-380.

Lesley Rigg

Rigg, L.S. (2005) "Disturbance processes in

maquis and forest, and the resulting spatial patterns of two emergent

maquis conifers, New Caledonia" (In Press Austral Ecology)

Rigg, L.S. and S. W. Beatty (2004) "The

abundance and spatial distribution of herbaceous and woody vegetation

along old field margins in three upstate New York fields" The Great

Lakes Geographer. 11(1): 54-65.

Rigg, L.S. (2003) "Genetic Applications in

Biogeography: An introduction." Physical Geography, 24(5): 355-7.

Diochon, A., L.S. Rigg, D. Goldblum, and N.O.

Polans (2003) "The regeneration dynamics and genetic variability of

sugar maple (Acer saccharum [Marsh.]) seedlings at the

species' northern growth limit, Lake Superior Provincial Park, Ontario,

Canada." Physical Geography, 24(5): 399-413.

Susy Zeigler

Ziegler, Susy Svatek. 2004. Composition,

structure, and disturbance history of old-growth and second-growth

forests in Adirondack Park, New York. Physical Geography 25 (2): 152169.

Back to the top.

Research Notes

Lesley Rigg,

Department of Geography, Northern Illinois University.

Biogeography and Beamtime

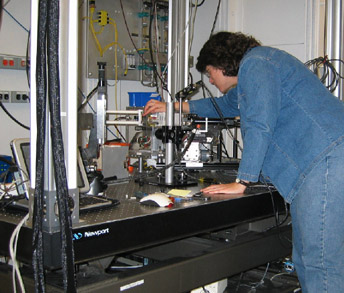

In conjunction with Dr. Melissa Lenczewski from the Dept.

of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at Northern Illinois

University, we recently initiated a project in New Caledonia examining

the role of the microbial community in vegetation change and structural

associations. We received funding from the American Association for the

Advancement of Science and the National Science Foundation: Program for

Women in International Scientific Collaboration (great program!).

In conjunction with Dr. Melissa Lenczewski from the Dept.

of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at Northern Illinois

University, we recently initiated a project in New Caledonia examining

the role of the microbial community in vegetation change and structural

associations. We received funding from the American Association for the

Advancement of Science and the National Science Foundation: Program for

Women in International Scientific Collaboration (great program!).

This work built on previous biogeographic research on species in New

Caledonia such as the endemic conifer Araucaria laubenfelsii.

Last year we were granted beamtime at the Advanced Photon Source (APS),

Argonne National Laboratories, to examine the uptake of nickel by Araucaria

laubenfelsii.

Along with a NIU PhD student, Linda Jones, we have now completed out

third set of beamtime (150 hours) and have expanded our research to

examine the uptake, location, and storage of, trace chemicals and

metals in trees growing in contaminated soils in northern Illinois. We

are working with a great team at Argonne (GeoSoilEnviroCARS, Dr. Steve

Sutton and Dr. Matt Newville) and we are currently attempting to

analyze our copious quantities of data!!

|

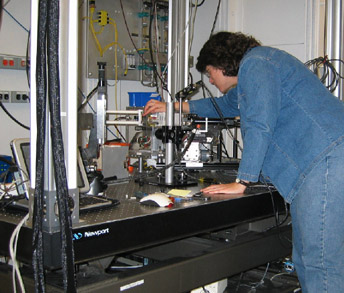

|

| Putting a sample in the hutch. |

Monitoring the results: Linda Jones on the left. |

For more information

http://www.lightsources.org/cms/?pid=1000166#section3

http://www.aps.anl.gov/

http://cars9.uchicago.edu/gsecars/GSEmain.html

Hartmut S. Walter

University of California-Los Angeles

Hart Walter continues to maintain a skeptical view of general and

global concepts in biogeography. He is currently working on regional

case studies that can illustrate the relevance of the geographic place

as part of the ecological niche (termed eigenplace). He is also working

on biogeographic aspects of extinction and presented a plenary paper on

the Culture and Politics of Extinction at the recent biennual symposium

of the International Biogeography Society. Two of his recent papers

reflect his critical analysis of biogeographic paradigms:

Walter, H. S. 2004. Understanding places and organisms in a changing

world. TAXON 53:905-910.

Walter, H. S. 2004. The mismeasure of islands: implications for

biogeographic theory and the conservation of nature. Journal of

Biogeography 31:177-197.

Regionally, he is currently spearheading an ESA petition drive with

UCLA undergraduates to save the endemic, unprotected and tiny remnant

population of the island loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus

anthonyi) on the northern Channel Islands off Santa Barbara, CA. For

details, see:

Walter, H. S. 2005. Extinction at our doorstep: what happened to the

island loggerhead shrike? Western Tanager 71 (4):1-3.

Henri Grissino-Mayer

University of Tennessee

The Baltimore Sun (February 4, 2005; E1) reported on Henri Grissino-Mayer's

collaboration with ORNL colleague Madhavi Martin to match pieces of wood found

with the body of a homicide victim with others connected with the suspected

killer. Investigators contacted Henri to see if he could match the two sets

of samples based on tree rings. The wood turned out to be mesquite, which doesn't

form good rings, but Henri contacted Madhavi Martin at Oak Ridge, who uses laser-induced

breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) to identify the geographic origin of imported

wood from Canada. The samples did, indeed match. The suspected killer has already

confessed, but prosecutors may use the evidence when the case goes to trial

later this year.

LIBS has been used to analyze soil

carbon and nitrogen, and may hold great promise for biogeographic research.LIBS

woks by using a high-energy pulsed laser to vaporize small amounts of a bulk

sample and optically excite the constituent elemental species of the resulting

vapor plume, and then recording the time-sensitive ultraviolet-visible emission

spectra of the elements as they de-excite. The result is a ppm-range multielemental

microanalysis of the sample, collected instantaneously with minimal sample loss

and little or no sample preparation. Researchers at Oak Ridge are currently

working to develop a field-deployable unit that could greatly expand opportunities

for biogeochemical research. (See Lesley Riggs' Research Note above).

Meral Avci

Istambul University

Dr. Meral Avci, did a dendrochronological studies in west part of Black Sea

Region (Turkey) that was financially supported by the Research Fund of Istanbul

University (Project number: 1780/21122001). In this research, the air pollution

which effects on annual ring widths of forest trees are tried to be determined

in Catalagzi surrounding (July 2004). Within the scope of this study, tree’s

increment corer samples were obtained from some locations to the south, east,

and west of Catalagzi Thermal Power Plant. She investigated a correlation between

annual ring widths and air pollution; annual ring widths and climatic components.

Width of annual tree rings might decrease because of the air pollution effect

in Catalagzi Thermal Power Plant surrounding, but site characteristics are better

than any place (humidity climate, deep soil etc.). So, this caused the decreasing

of the damage degree.

|

|

|

Catalagzi Thermal Power Plant in west part of

Black Sea Region (North Turkey).

|

Dr. Avci, in Catalagzi |

For more information, contact

Dr. Meral Avci

Istanbul University,

Letters Faculty, Geography Department

Laleli/Istanbul

e-mail: mavci@istanbul.edu.tr

Back to the top.

Field Notes

Saskia van de Gevel and Evan

Larson; Advisor: Henri Grissino-Mayer

University of Tennessee

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis Engelm.)

is a long-lived tree species found in many high elevation and subalpine

forest communities of western North America. Twentieth century fire

suppression, periodic mountain pine beetle outbreaks, and white pine

blister rust infestations have led to dramatic declines in whitebark

pine communities throughout the species’ native range, with critical

ramifications for dependent wildlife species. To better understand the

dynamics of these declining communities, we are investigating (1)

current and past stand dynamics, (2) the role of wildfires and the

effects of its exclusion, and (3) the synergistic effects of various

disturbances and climate in several locations in western Montana.

During a month-long expedition during the 2004

field season, we collected stand and fire history data on three

mountains in the Lolo National Forest, near Missoula, Montana, and on

one peak in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest along the border

between southwestern Montana and Idaho. Thanks to Elaine

Kennedy-Sutherland, we also attended a workshop on monitoring white

pine blister rust in whitebark pine forests, presented by the Whitebark

Pine Ecosystem Foundation in West Yellowstone. Analyses of our samples

have thus far yielded a 1000-year whitebark pine tree-ring chronology

that dates well against previously-developed whitebark pine

chronologies in Idaho. The fire histories for each mountain include a

combined 150 fire scars and 70 unique fire events over the past 600

years. We have presented our preliminary results at the Whitebark Pine

Ecosystem Foundation Meeting in Waterton, Canada in September of 2004,

and look forward to presenting our recent findings at the Association

of American Geographers Annual Meeting in Denver this April.

This research was

funded in part by the 2004 Biogeography Specialty Group Research Grant

awarded to Evan for his Master’s thesis research. The grant was used

for travel, field equipment, and for several layers to help ward off

the early June weather of the high country. Thank you!

Saskia has been

awarded a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research

Improvement Grant to continue her research on whitebark pine stand

dynamics for the next two summers.

|

|

| A whitebark pine at the edge of a plot on the

slopes of Ajax Peak, in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest,

Montana. |

Henri's first day in the field with us began with a soggy camp and whiteout

conditions on top of Point Six, but we still managed to put in a good

day of work! |

Back to the top.

Book Notes

Book Notes highlights recent books written by, or of special

interest to, BSG members. Reviews and suggestions welcome.

Review

Susan Woodward

Biomes

of Earth: Terrestrial, Aquatic, and Human-Dominated.

2004. Greenwood Press. 456 pages, maps, photos, tables. List price: $79.95 (USD).

ISBN: 0-313-31977-4.

and

Lori Daniels

Biogeography

Image Exchange: Explore the World's Biomes

Explore! CD. List price $10.00 (USD).

Anybody who has

ever

considered creating an introductory course on comparative biogeography

has

probably abandoned the idea after searching, and not finding, a

suitable

textbook. There are several biome books and reference volumes aimed at

K-12

students, and more advanced-level volumes devoted to specific biomes,

but there

is no current text devoted solely to comparative biomes and written for

an

undergraduate audience.

Susan Woodward’s Biomes of Earth: Terrestrial, Aquatic, and Human-Dominated

fills this long-standing gap in the physical geography

textbook market with a comprehensive and reasonably priced undergraduate (and

advanced high school) textbook. The book grew out of Woodward’s contribution

to the Virtual Geography

Department which promised, back in the heady early days of the web, to supplant

commercial textbooks by promising free access to constantly up-to-date and massively

hyperlinked online content. Publishers were understandably nervous about such

ventures, but as it turned out, they needn't have worried. The Virtual Department

fizzled, for the most part, but old-fashioned publishing seems to be doing fine.

Fortunately, Greenwood Press has seen fit to "rescue" one of the brighter pieces

of the failed virtual revolution and deliver it to us in the form of a promising

textbook.

Biomes of Earth

is both

predictable and surprising. Predictably, the book consists of an

introduction,

followed by chapters devoted to individual biomes. It is structured in

four

parts, with separate sections for terrestrial, freshwater, marine, and

human-dominated biomes. Each section begins with an overview that

covers basic

concepts and terminology used in the subsequent chapters. Each biome

chapter

follows a standard format that begins with a map and overview, and

includes

subdivisions covers climate, vegetation, soils, animals, and regional

expressions. And like most textbooks Biomes

has key terms set in bold type and defined in a glossary, is sprinkled

with (black

and white) photographs, is indexed, and includes a bibliography. Given

the

finite limits of a single introductory textbook, the coverage is

predictably

broad and shallow.

These are not weaknesses. Lack of depth is unavoidable

given Woodward’s goal of creating a comprehensive introductory textbook

on an immensely broad, diverse, and complex topic. The book’s predictable

format and rigid structure impose discipline that keeps it from sprawling and

give it unity coherence that students will doubtlessly welcome and that should

facilitate course construction.

Biomes’

surprises are more

interesting, and potentially more limiting, than its predictability.

The

introduction focuses on the biome concept and its historical

development, but

it treats the latter in more depth than most science textbooks do.

This,

together with a good discussion of taxonomy, helps emphasize the fact

that

biomes delineations are human constructions and subject to degrees of

arbitrariness. I would have liked to see this theme developed more

completely,

with at least a few examples of different biome classifications

included. I

think an explicit discussion and concrete examples of scale and

resolution

issues, and of distinctions between communities, ecosystems,

ecoregions, and biomes

would be useful as well. Similarly, I found that some sections presume

more

background knowledge than I would expect from most of my students. I

noticed

this particularly in the soils sections, and I can imagine students

being

frustrated when they encounter terms (e.g. “A horizon” and

“podzolization”) that

are not included in the glossary or index.

More pleasantly, I did not expect to see chapter

subsections devoted to the origins or the history of scientific exploration and

research of each biome. These add depth and interest to the volume. Likewise,

most treatments (I am thinking primarily of general physical geography, biogeography,

and ecology textbooks) either ignore or skimp on coverage of aquatic biomes, but

Woodward devotes nearly a quarter of its pages to these critical environments.

Doing so is risky, since it necessarily limits the thoroughness with which she

can treat of the terrestrial biomes that generally occupy geographers’ attention.

But most of the globe is ocean, and like the biosphere itself, physical geographers

probably give it less attention than we should.

Perhaps the

biggest surprise

is the inclusion of a separate section devoted to human-dominated

biomes

(agroecosystems and urban ecosystems). Woodward acknowledges the

idiosyncratic

and experimental nature of this inclusion, and I think it works well,

especially in concert with each of the other chapters’ human impacts

subsection.

Finally, I was surprised

at the near total reliance on verbal description to convey information. While

Dr. Woodward's descriptions are particularly lucid and effective, Biomes does not include any graphs, contains no maps except

those for individual biome distributions at the beginning of each chapter, and

has very few tables. Reference maps showing the Koeppen climate distributions

all of the biomes at once, and possibly shaded relief and place names referred

to in the book would, I believe, greatly enhance the book’s usefulness.

They could also free up some of the space devoted to describing information

better conveyed visually. Likewise, quantitative data (in the form of maps,

tables, or graphics) on net primary productivity, standing biomass, soil carbon,

and other factors would greatly facilitate comparisons among biomes and between

biota and physical environmental factors. Even a few more graphics and tables

could greatly enhance the book’s information and increase its density

and depth.

All of these lacunae could easily be addressed

in lectures and supplemental handouts gleaned from other textbooks, but I hope

that future editions of Biomes will incorporate them directly into the text. A more

thorough index and glossary would also be welcome. Overall, Biomes of Earth is

well thought out and executed. The writing is clear and accessible, and both the

text and photographs draw on Dr. Woodward’s extensive experience, travels,

and research. It should appeal to and work well for most undergraduate students,

could spawn a boom in comparative biogeography courses, and deserves a place on

any biogeographer’s bookshelf. Susan Woodward and Greenwood Press deserve

kudos for this fine contribution to the biogeography literature.

The photographs

in Biomes

of Earth are all black and white, and

even

though most of them are clear enough and well-printed enough to work

perfectly

well, students will doubtlessly appreciate a little color.

Fortunately,

Lori Daniels’ Biogeography

Image Exchange project is now available on CD as well as

on the web,

and makes a perfect companion to Susan Woodward’s book. It is also a

fantastic

resource for putting together lecture slides.

The exchange

includes nearly

500 photographs contributed by BSG members. Each image includes a brief

annotation, and the collection is searchable

by biome/vegetation

type, latitude/longitude, or by the contributing biogeographer’s name. The

coverage is uneven and ranges (at this point) from a mere ten wetlands

photos

to 151 images in the

Needleleaf Forest category. This is a minor problem, however, given the

many upsides to the project. What's more, you

can help expand this coverage by contributing your images to the

project.

The CD costs $10

(US) and

includes higher-resolution images than the web site. Best of all,

proceeds from

sales of the CD go to the BSG’s Student Awards program.

Reviewed by Duane Griffin

New Books

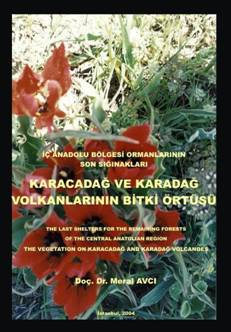

Avci, Meral. 2004. The Last Shelters for the

Remaining Forests of the Central Anatolian Region, The

Vegetation on Karacadag and Karadag volcanoes. Istanbul: Published

by Cantay (In Turkish, also English abstract), 16X24, XI+168 page,

ISBN: 975-7206-99-7.

Avci, Meral. 2004. The Last Shelters for the

Remaining Forests of the Central Anatolian Region, The

Vegetation on Karacadag and Karadag volcanoes. Istanbul: Published

by Cantay (In Turkish, also English abstract), 16X24, XI+168 page,

ISBN: 975-7206-99-7.

The Central Anatolian Region is a vast area

without forests where steppe vegetation is widespread, especially in

comparison to Turkey's coastal regions. Geomorphic processes and other

growth conditions have played an important role in the distribution of

the plant formations in this region.

The

region's climatic characteristics enable tree growth outside of local

natural steppe areas, where human impact as well as natural conditions

have shaped the plant formations. When the whole Central Anatolian

Region is taken into consideration, natural steppe areas, which cover

relatively small parts, have expanded due to human impact

on forests (agriculture, heavy grazing, fires etc.). In this

way, many steppe plants have invaded deforested areas and been

naturalized there. On the other hand, relatively high mountains in this

vast and seemingly treeless region have been the shelter-refuges for the last remaining forests of the Central

Anatolian Region. These mountains include Karacadag

and Karadag volcanoes, which have significant forests that are notable

for their high species richness and endemicity,

reflected in the specific epithets volcano and vulcanicum applied to some of the plant species first collected

from Karadag

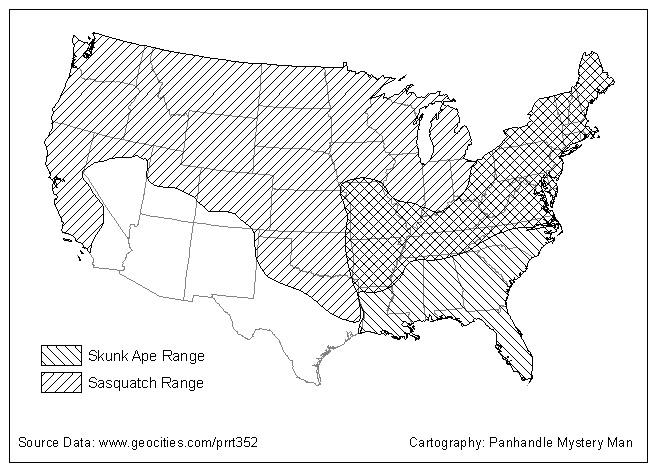

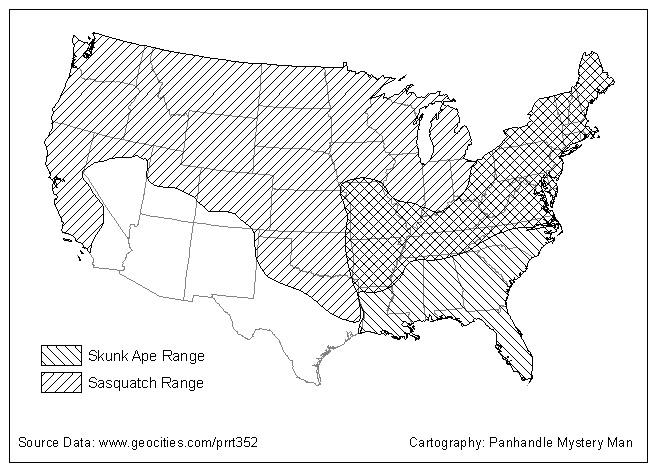

Map

Bigfoot subspecies range extents in the continental

U.S.

Editor's Note

As always, thanks to everybody who contributed material to this edition, and

a reminder to contribute to the next one. News items, book reviews, or anything

for the Notes sections are always welcome.

Your editor enjoys putting the newsletter together twice a year, but I could

use some help. Specifically, I'm looking for somebody to keep track of member

publications and help assemble and edit the Notes sections. If you can spare

a few hours each fall and winter, let me know. No special skills are necessary.

See you in Denver!

Duane A. Griffin

Editor, The Biogeographer

Bucknell University

Dept. of Geography

Lewisburg, PA 17837 USA

570/577-3374

dgriffin@bucknell.edu

Back to the top.

The performances and conducting of Serge Koussevitzky

(1874-1951) gave the world its first serious exposure to the double

bass instrument. In 1962, after hearing a New York Town Hall recital

given by Gary Karr, Koussevitzky's widow, Olga, gave Karr the double

bass used by Serge Koussevitzky, reportedly made by Antonio and

Hieronymous Amati in 1611. The Amati brothers were sons of Andrea Amati

who began the famed Amati line of instrument makers in Cremona, Italy,

in the mid to late 1500s. Nicolo Amati (1596-1684), the son of

Hieronymus, was the mentor of Antonio Stradivari.

The performances and conducting of Serge Koussevitzky

(1874-1951) gave the world its first serious exposure to the double

bass instrument. In 1962, after hearing a New York Town Hall recital

given by Gary Karr, Koussevitzky's widow, Olga, gave Karr the double

bass used by Serge Koussevitzky, reportedly made by Antonio and

Hieronymous Amati in 1611. The Amati brothers were sons of Andrea Amati

who began the famed Amati line of instrument makers in Cremona, Italy,

in the mid to late 1500s. Nicolo Amati (1596-1684), the son of

Hieronymus, was the mentor of Antonio Stradivari.

In conjunction with Dr. Melissa Lenczewski from the Dept.

of Geology and Environmental Geosciences at Northern Illinois

University, we recently initiated a project in New Caledonia examining

the role of the microbial community in vegetation change and structural