Shikellamy

|

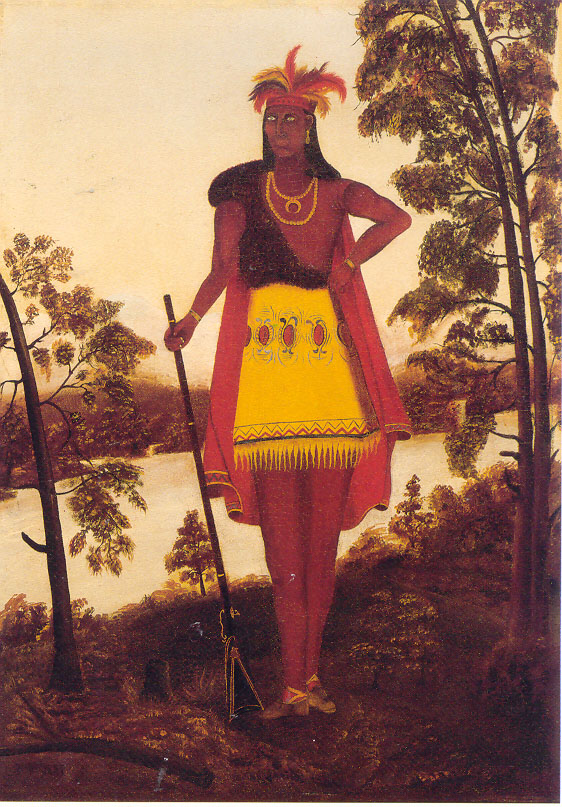

Shickellamy’s origins are controversial. Some say he was from France, but taken captive by the Indians when he was child. Others claim that he was a Susquehannock by birth, a descendent of the Andastes, who was adopted by the Oneida tribe and due to his valor in war was eventually named chief. What is known with certainty is that in 1727 when the Iroquois took control of the west branch of the Susquehanna River, and began to govern Shamokin, they sent Shickellamy to serve as resident viceroy over the great Indian town. It was their intention that he would care for all of the Indian’s residing along Pennsylvania’s border. Thus the Delaware, the Shawnees, the Nanticoke (or Conoy), and the Conestoga (formerly known as the Susquehannocks), looked to him to guide, direct, and settle disputes. Meanwhile the provincial leaders of the time liked to think that he was sent to keep the Shawnee in line, and since they had trouble exercising authority over the rebellious tribe themselves, they were thankful for his help and respected his leadership. The European’s admiration, combined with the friendship he established with Moravian missionaries in the town and his Indian authority, made him the perfect candidate to serve as an Iroquois interpreter, ambassador, and contractor among the English in Philadelphia. |

| : Shikellamy’s name means “He who causes it to be light” or “enlightener”. Shikellamy enlightened others through his friendships and treaties and worked to keep the peace between the Natives and the Europeans. At times he has also been referred to as Swatany. |

His first entry into political history in Pennsylvania documents occurred in 1732 when he was called to Philadelphia to serve beside Conrad Weiser as a mediator among the Six Nations and the whites. This led to a life long devotion and comradeship. Working along Weiser, Shickellamy became the most respected and frequently employed Indian interpreter and ambassador of his day. Although he could not read or write, his sensitivity, tact, and control made his word law. In 1747 a Moravian missionary wrote, “Shikellamy, at this date, is emperor over all the kings and governors of the Indian nations on the Susquehanna”. He maintained the balance of power between the different tribes and acted as Agent of the Iroquois confederacy in all affairs of state and war. Much of his success stemmed from his competency of working with the Europeans instead of working against them and he was especially gifted with keeping peace among the Shawnee, who were impatient with Iroquois rule and angry at the British for being misplaced. In short Shikallemy was in charge of supervising the entire Indian population of central Pennsylvania (Everts, 27); he was considered chief, king, superintendent, deputy, emperor, and magistrate of the Indians.

When Shikellamy accepted his leadership position he was not looking for profit or reward. He was not given food, money or protection, as English governors were. He was still expected to hunt and fish for himself, build his own home, and bar his door at night. While the position was considered an honor, it was mostly a responsibility to which he would be held accountable. The only payment Shikellamy ever received was in October of 1747 when, bedridden with disease, Conrad Weiser insisted that the council pay him the equivalent of sixteen pounds: he received match coats, gunpowder, lead, knives and other tools.

Though not much is known of Shikellamy’s family, records reveal that he was married and had several children. One son is recorded to have died in 1729, and a second, “Unhappy Jake”, was killed by the Catawbas in 1743. In the autumn of 1747 an unidentified “feaver” afflicted his family: his wife, one daughter-in-law, one son-in-law and eight grandchildren were killed at Shamokin. Shikellamy was also subject to the disease, but received medicine from Weiser that was able to extend his lifespan. After several cycles of recovery and relapse, during which time he traveled to Tulpehocken, Philadelphia and Bethlehem, he was eventually overtaken on December 17, 1748. Having been baptized into the Christian faith by his Moravian friends, he was attended on his deathbed by Zeisberger, a religious leader. Shikellamy died on December 17, 1748. He was buried along the river.

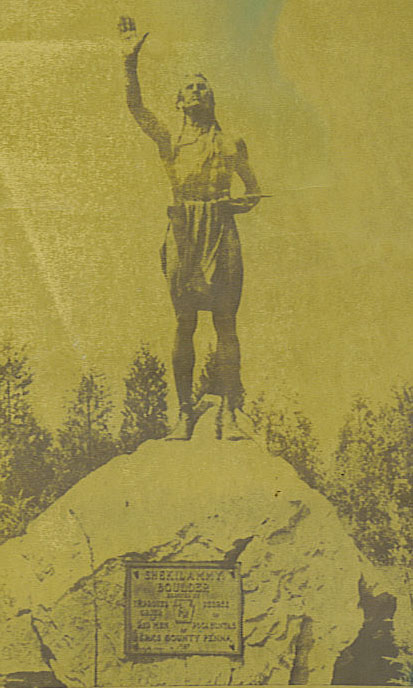

Shikellamy resided in Shamokin between 1737 and 1743. While the exact site of his burial is uncertain, a stone has been erected in his honor and can still be viewed today (directions).

|